In 2012, it became abundantly clear that a lot of people around the world had no clue that Mayas are still living among them. I will never forget the look on a young man’s face when I confirmed that indeed, the Mayas do exist. It was a novelty for him, and being that it was the much-buzzed about ‘2012: end-of-the-world”, his curiosity led to asking, “How do you live?”

I take that question and add to it, “How do we continue our traditions and way of life in a modern society?”

The answer is a bit complex, as we are now far-flung through the corners of Belize, and many other countries around the world. One thing we have in common, beside our language, is our love for home, Tanah. I was born and raised in San Antonio Village in the Cayo District. The westernmost district is home to some of the most beautiful landscapes, and in my humble and biased opinion, San Antonio is nestled in one such spot: a valley ringed by mountains as far as the eye can see, homes dotting high hills and dirt roads snaking every which way.

(r) Dr. Elijio Panti

The population is primarily Yucatec, and I am fortunate to have been born in the era of one of the most famed healers, Dr. Elijio Panti. I also grew up with the Garcia Sisters, who had their brush with fame with their slate carvings and art. In fact, one sister continues pushing for tradition and preservation of culture, lobbying alongside other villagers to honor Dr. Panti with a medicinal trail/reserve. Another group of hard-working artisans have taken on the magnificent art of pottery-making, using the help of a New York University professor to create bowls and figurines in homage to our ancient ancestors’ styles. We speak our Mayan language, conversing wherever we meet, be it in the center of the village, or on this very island where I now reside. We can pick each other out, bound by a common thread…and we talk and reminisce.

One of three

There are three confirmed groups of Maya in Belize: Yucatec, Mopan and Ke’kchi.

I’m the product of a Yucatec Maya man and Creole/Garifuna woman, and identify as Maya.

Life in the village

Like so many children in the village, I grew up around a host of uncles and aunts and cousins. As an only child, I often gravitated towards my grandmother in her kitchen. In hindsight, Grandma was the tiniest wizened creature, but to a small child, she was the world, bigger than life itself.

Her thatched kitchen was made of skinny logs, wide open doors and windows so the smoke from her fogon (fire hearth) would get out easily. Directly overhead, the thatch was ebony black with soot from the wood smoke. I remember seeing long strips of deer meat often draped on a line high above the fire, curing and smoking for many days. The day she would bring down the meats, it was feasting time.

El Fogon

Sometimes I’d help pick the brightest habaneros from the tree just outside, and she would pick tomatoes ripe on the vine. After raking some coals off to the side, she would add more wood to the fire and her comal would be placed to heat up. Freshly washed habaneros were dropped directly on the separated coals, spitting and hissing as they got charred and their scent filled the air. Tomatoes roasted atop the comal as well. Some fresh cilantro would be chopped, along with shallots grown in the backyard garden.

Grandma would smash the hot habaneros with generous sprinkles of salt and fresh lime juice, using a homemade wooden pestle. Cilantro and onions would get added, and being the fearless woman she was, she’d stick her finger in the bowl and taste! The roasted tomatoes got a similar treatment, with just a tiny bit of the habanero sauce added to give it a little kick.

There was always masa (corn dough) ready to go, and she would start patting out round stacks of hot and fresh tortillas. When the stack was ready, often in danger of toppling over, she would sit at the table, shredding her portion of the shredded smoked meat, dabbing handfuls in both sauces, wrapping with a hot fresh tortilla and savoring it with her eyes closed.

Today, the joy of a hot fresh corn tortilla is still enjoyed, whether from a fire hearth or stovetop, it still is about making our own food.

Where were the men?

Culture and tradition in many Latin-American countries have often led to the idea that the men do the hard labour in their milpas (farm) while the women stay at home and tend to home and children. Grandma had a total of 16 children, of which 10 survived to adulthood.

Like in many families, our mornings began before the sun rose. Children often slept through the clatter and bang of the kitchen as mothers and grandmothers prepared a hot breakfast and lunch for the man/men of the house. During school days, it was only the father, but at holiday time, so long as you could walk through a grove of corn, you could help carry something, and children and all were packed up and taken to do some milpa work!

After packing scrambled eggs, perhaps some beans in a bowl and a few fresh tortillas, a recycled bottle filled with milky coffee, the men would pull on their long-sleeved shirts, tuck in their pants into their rubber boots, tie their scabbards carrying extra-sharp machetes, and if they were feeling lucky, they would also sling a rifle over their back. At the top of the mountains due east, the first rays of sunshine would start sending some light. With one foot on the stirrup, and a quick swing of the leg, they would take off, the morning air filled with the clip-clop of horses all headed to parts deep in the jungle. By the time they broke through the thicket of trees and crossed creeks, the sun would be blazing on the rows and rows of their crops: peanuts, corn, onions, cabbages, watermelons, peppers, tomatoes…whatever it was that they decided to plant.

At home, those who saw the rifle being slung over would wait to hear the shot. Often, there would be a loud boom, which would echo from mountain to mountain, and the question was usually, “Who? And did they get it?” Today, the sound of a gunshot ringing through the valley still brings a frisson of excitement for those eager to have some game meat.

Folktales

When everyone was settled home, and there didn’t seem to be much work to do, the gathered children would sit at the feet of our wizened old grandma, listening to the folktales passed down from generation to generation. There was nothing better than getting the full story of the Alux (A-loosh)/Tata Duende, the Xtabai (Ish-tah-bye) or the Cadejo (ka-de-ho).

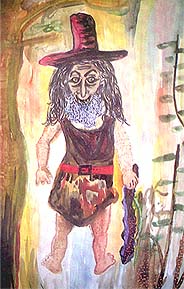

El Tata Duende

For us naughty kids, the Alux story would ALWAYS get to us. Tales of the tiny man luring badly behaved children into the jungle with him were terrifying, as were the stories of him riding horses for fun, braiding their manes so impossibly tight that owners would have to cut them off. The stories always ended with a warning to: listen to your parents, don’t wander off alone…and well, I’m still not sure what the poor horses could have done to avoid their braided manes!

El Cadejo

When we witnessed tightly braided horse manes, the stories of the Alux would come back to us, bringing chills up and down our spines. Perhaps they were real, perhaps not; there isn’t much to say that we don’t walk a fine line between fantasy and reality. If nothing else, Grandma told us these stories as a warning to behave, and for the chuckles she got watching a group of four or five grandchildren walking each other to use the outhouse at twilight!

The others

We’ve always been aware of other Maya people in the rest of the country. At one point, my grandfather panned for gold, going away for weeks on end, deep in the jungle. He would come back with stories of other villages where the people spoke Maya. He described them as completely different from us…many of them running away and hiding from the group of gold-diggers. He said their language was different, Maya, but different. Later in our Social Studies class, we would learn more about the Ke’kchi Maya, who primarily populate the southern district of Belize.

Nowadays, they, along with the Mopan, continue living among the other ethnic groups of Belize, adapting to modern life while maintaining their traditions and continue to proudly share their culture with the rest of the world. So, to answer the original question, “How do we live?”

The answer is simple: happily…proudly…contentedly. It is a beautiful thing to be Maya.