Reprinted with permission from author Janelle Chanona, Vice President Oceana in Belize

Oceana in Belize has been busy instilling a sense of wonder and stewardship for the oceans in Belizean youth. Earlier this month, they took a group of under-provided boys, all under the age of 14, to Belize’s beautiful coral isles. For many of them, it was their first time to the ocean — meaning it was the first time that they were able to see this famous, stunning resource of their own country. Their reactions alone tell the story of just how much of an impact calming waves and charismatic ocean wildlife can have on someone.

Vice President of Oceana in Belize wrote a heart-warming account of this special weekend at the Lighthouse Reed Atoll, and has generously shared it with our My Beautiful Belize readers.

Social media consistently bombards us with quotes, poems and catch phrases meant to inspire. Most of them fall miserably short. But I’ve found that every once in a while an experience transforms a simple saying into a profound truth. And as I reflect on this weekend’s events, emotion overwhelms my eyes at the thought of Jacques Costeau’s, “The sea, once it casts its spell, holds one in its net of wonder forever.”

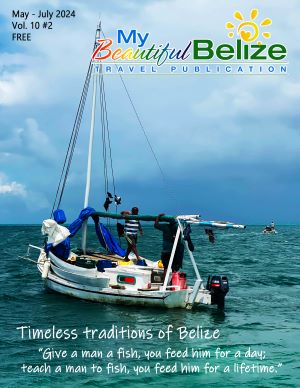

One of the youngest of the group had a shy smile, short stature and a bullet wound. They have all known various levels of violence. They have each seen and felt things no child should have to. And they are all less than fourteen years old. But as the boat put more distance between them and the tough streets of the old capital, the open sea began to break down their youthful bravado. The inevitable excitement of experiencing something for the first time lifted their spirits high into the salty wind and by the time Belize City disappeared from the horizon, their electric energy was helping to propel us forward.

The journey to the Lighthouse Reef Atoll has intimidated more than a few Belizeans; orange jackets doing little to comfort the fears of the blue depths beyond the Barrier Reef. But my young companions’ eyes are filled with curiosity, not fear, as they beheld the stunning color palette of the Caribbean Sea. The brown tones of the only sea they’d known, the “hangar,” easily replaced by more blues than a box of crayons. The immersion of color continued as the always picturesque Half Moon Caye appeared on the horizon: green and yellow coconut fronds swaying above a sandy white shore while red footed boobies and magnificent jet black frigates dot a cloudless turquoise sky.

It’s a scene that calls to one’s soul. And the boys can’t wait to soak in the moment. Minutes later they dive into the sparkling, salty water, eager to show off their swimming, splashing, and floating abilities. The sound of their carefree laughter carries above the constant crash of waves. The salt stings their eyes but there are no complaints. The sound of the ebb and flow of the coral beach mimics applause. This trip has been years in the making and I cannot understand why. Belizeans enjoying Belizean resources is truly priceless.

Suddenly their need to know more is irrepressible. What’s that fish called? How come corals are different colors? Why is my mask ‘smeary’? Hermit crabs like rice? Is that booby bird sleeping? Who waits up at night for the turtles? Can I study turtles now? Why is the Blue Hole blue? When will we see a shark?

Why do we have to go home? That last question is the most telling of the impact the trip has made but it’s also the hardest to answer. I am forced to ask my own question: Will this spark of light ignited hold its own in the dark reality of life as they know it? The open-ended question hangs heavy in the air as I stare up at the full moon.

“Turtle!” The single word rouses me from deep, salt-induced sleep into a state of high alert. I am breathless but it’s not from running headlong into the night. A nesting turtle is a sacred moment in nature and I am overcome by the honor of silently witnessing her contribution to the world. Earlier on the beach, I had laughed as the boys pretended to be turtles preparing their nests. Watching it happen for real proved surreal. Painstakingly the hawksbill dug deep into the sand with her flippers. Awash in the bright moonlight, it was clearly evident that she grew tired with each stroke. Finally the sound of cascading sand against her shell gave way to a unique quiet. The laying had begun.

Research shows hawksbills can lay as many as 250 eggs. I couldn’t tell all that from my perch but I got goose bumps just from knowing it was happening just a few feet away. Minutes later the movement started again. This time, the mother used her flippers to cover the clutch of eggs. I am awestruck; this would be an arduous task for even someone with hands. The hole that took her almost an hour to dig is carefully covered within fifteen minutes. Slowly the turtle turns and drags herself across the beach and into the sea.

As I watch her disappear beneath the waves, I ask her to take my fervent hopes with her: The hope that one day we will all be spellbound by the sea and its magical moments; the hope that one day every Belizean—man, woman and child—will come to know Belize’s wealth of natural resources; and the hope that somehow she heard my whispered but heartfelt “Thank you!”